Agency: High in Lunana, where icy winds cut through valleys and yaks are the only steady companions, a quiet but daring experiment is underway. It may decide the safety of thousands living far below.

Thorthormi Lake, Bhutan’s most feared glacial giant, has become increasingly restless. Once a glacier studded with pockets of meltwater, it is now a vast moraine-dammed reservoir, swelling and shrinking unpredictably. Each year, as Himalayan temperatures climb, the lake deepens, and sometimes rising by meters, other times dropping, its mood as uncertain as the climate driving it.

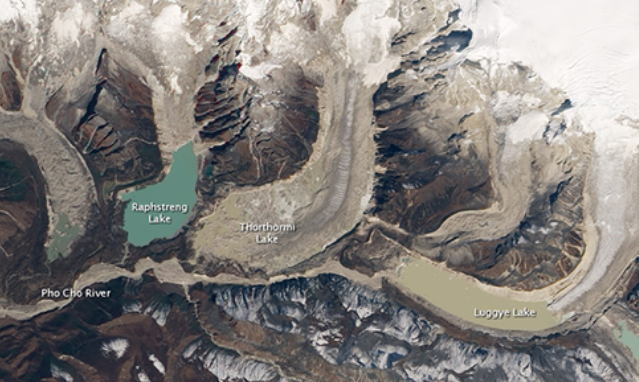

Two incidents in 2019 and 2023 gave Bhutan a frightening preview of what could happen. The lake spilled into Pho Chhu, swelling the river overnight before calming again. Both times, disaster was narrowly avoided. Yet the danger is real, Thorthormi sits directly above Rapstreng Lake, separated only by a fragile moraine wall that has already shrunk from 45 meters in 2008 to 33 meters by 2019. If it collapses, the two lakes could merge, releasing 53 million cubic meters of water, a torrent powerful enough to wipe out villages downstream.

This year, Bhutan is attempting something never tried before in such harsh terrain, siphoning water from Thorthormi using gravity-powered pipes. Unlike past operations where hundreds of workers toiled for years with shovels and pickaxes, this method uses helicoptered-in HDPE pipes to draw water out, powered only by gravity. The test phase began earlier this month and will continue until 29th October.

For Bhutan, the stakes could not be higher. The siphon system requires no fuel, no machinery, and can even function through winter, vital as Thorthormi no longer freezes solid. If successful, it could become Bhutan’s long-term defense against glacial floods. If not, the country may be forced to return to old, labor-heavy methods, even as the waters continue to rise.

For the people of Lunana, this is more than a technical trial, it is about survival. Thanza’s primary school has already been moved after the 1994 Luggye Tsho disaster killed 21 people. Families continue to relocate, living in tents buffeted by Himalayan winds. “We live every summer watching the mountains, never knowing if the lakes will break,” one villager said during the last monitoring mission.

Meanwhile, recent cloudbursts in northern India, triggering flash floods and landslides in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, are grim reminders that the Himalayas are entering an era of extreme water disasters. Bhutan, with its fragile geography and 17 potentially dangerous glacial lakes, is at the frontline of this crisis.

At the heart of the current mission are hydromet officers stationed in Thanza. Their task is both technical and emotional, monitoring the lakes, collecting data, and ensuring timely warnings. Among them is Nedup Dorji, newly appointed this season, who now carries the responsibility of ensuring that life-saving alerts reach the communities downstream.

As the pipes are laid and the siphons tested, Bhutan is not just battling a lake, it is racing against climate change itself.